Around 12,000 years ago, the domestication of animals and plants began, as our ancestors moved from nomadic hunter-gathers to agriculturists. Mankind began exercising their mastery over all and nothing would ever be the same again. Thinking of ready sources of food, fashion and fun, lifeforms were altered according to man’s wants, needs and whims, which has culminated in where we are today.

Ancient grains of wheat were rapidly modified to the larger grains with their non-shattering spikes we currently enjoy. The wolf trotting by our side morphed into our beloved canine pals in all of their glorious shapes, sizes and loyalty; the magnificent Auroch was tamed into our modern breeds of cattle with their distinct suitabilities; and the agile wild Mouflon was to be selectively reworked into the fleeced sheep of today.

Fast forward to 1788, and thinking of ways to feed a fledgling nation, bulls, cows, fat-tailed sheep, goats, pigs, turkeys, geese, ducks and chickens were crudely trussed up like cargo and stowed onto the First Fleet. Those who survived the tumultuous voyage arrived, like their human contingent, worse for wear, as the penal colony of Australia was kick-started.

And impact the land the foreign imports did, often in deleterious ways that could not have been imagined, which leaves many of us today asking, “What were they thinking?”. As the number of domesticated animals flourished under human care, thoughts began to arise about ways to capitalise on this stroke of good fortune – thoughts of financial gain, but sadly, as history shows, not always of animal wellbeing.

Early records suggest 1845 to be the year the tide turned for the flow of animals to our shores, as the first sheep began to make long treks, often by rail, to be loaded onto boats and sent to foreign ports, cultures and climates. Despite this initial trade being fairly small, the treatment of animals did not escape the thoughts of those concerned with animal wellbeing. A letter appearing in the Brisbane Courier of October 10th, 1877 highlighted such concern. The letter writer concluded that “Surely this is a case the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals ought to investigate and prosecute the guilty parties without fear or favour. To confine animals for four days in crowded trucks without food or drink is as gross a case of cruelty as it is possible to conceive.” Not surprisingly, little comment was made about the onboard conditions the animals were subject to, as once on the boats, they escaped the public gaze and sadly too their thoughts.

The mid-1970s saw the live export trade surge, fuelled by demand from the Middle East. And I doubt there would be a person here today who has not heard of or seen the inerasable images of the litany of pain, anguish, despair and agonising death has been left in its wake. It was in May of 2011 when our thoughts were haunted by the heartbreaking images of Tommy, oh Tommy we will never forget you, Tommy a black Droughtmaster steer taken from the vast plains of his homeland and shipped to Indonesia where his final moments were captured on film. Trembling in terror and engulfed in absolute fear, he watched his buddies, one by one, butchered before his eyes. We saw what happened to Tommy and his kind, and empathised, recognising that regardless of the form one has taken, each and every being cherishes their life, feels fear and dreads pain and suffering. And in that instance the live export trade lost its social licence. This is an industry that has boasted large-scale reform, continuous improvement, yet repeatedly has shown it cannot be trusted. Heaven knows how low the bar must have been set.

And today atrocities within the live export trade are still being exposed, whether by industry insiders, from vets to crew members or through the work of not-for-profit charities such as Animals Australia. The live export trade continues to show that no amount of regulation or improvements can protect our animals from indescribable and unnecessary pain, suffering and death.

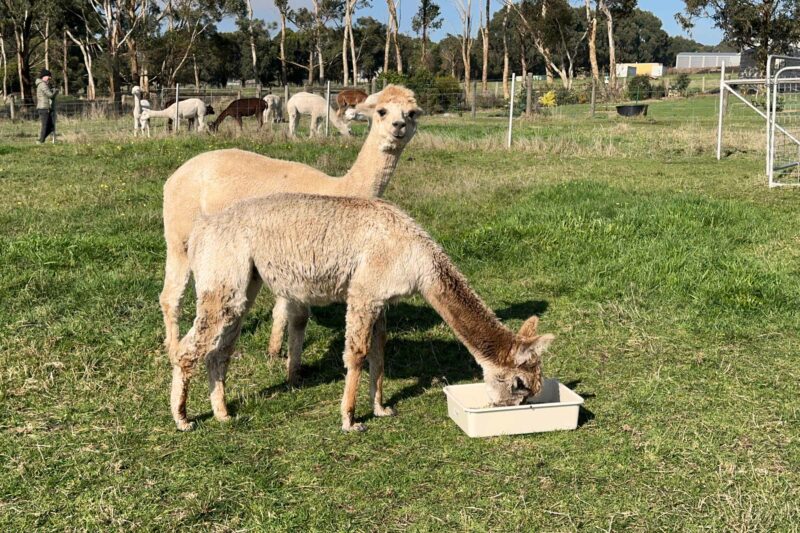

Such pain and suffering is brought into great focus for me through my work at Edgar’s Mission. Spending much of my life with my extended family of farmed animals as I have, I am truly fortunate to be able to lift a curtain into their world and, with a view unmarred by vested interest, peer deep inside. It is something I think every politician should do. See the friendships and strong bonds these animals form within their family and friends, even taking an honorary human into their mix now and then. See them at play, expressing curiosity and wonder for the world around them. See them transition from frightened and even aggressive to amiable and kind – although some reserve their right to be grumpy, and who are we to argue, after all their lives once at Edgar’s Mission are full of choices – theirs not ours.

I doubt there would be two people here today who have the exact same view on our place in the animal kingdom and the natural world, yet few would argue animals can experience pain. Society has acknowledged this too, enshrining it in legislation called the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act.

Yet as prey animals they are hard-wired not to show their pain in ways we can readily and visibly recognise. But make no mistake, this does not diminish their ability to experience it. What it does mean is that it conveniently and routinely goes unseen and unrecorded. To only measure poor welfare outcomes in terms of death, which is the industries want, misses an entire spectrum of poor states of being for these hapless animals.

Daily, as I am afforded a unique insight to the rich emotional world of farmed animals and in doing so see their individual personalities, I see they are each as diverse as our own. There’s Latini, who is forthright and bold, determined to go where no sheep has gone before; there’s cheeky little Milly, who has decided what’s mine is hers and that even includes my bed; there’s Clarabelle, who is so besotted with her baby she never lets her out of her sight even though her baby is four years old and bigger than herself.

So many animals I am fortunate to share my world with, and each known by name – this is something visitors to the sanctuary marvel at, in particular our ability to recognise each of our ovine friends. But what many find even more impressive is that sheep can recognise the faces of their friends, and when it comes to humans they can even distinguish between happy and angry faces too, and naturally just like us they prefer the happy ones.

With such knowledge of the complex social and cognitive capabilities of animals, which science, common sense and compassion now attest to, I can confidently say these animals are far from the dumb-witted beings many have thought them to be. Yet despite all our species has afforded animals, I truly believe in the goodness of the human heart. But somehow along our evolutionary path we have become blinded and desensitised to their suffering, and atrocities have occurred as we have failed to recognise the beating hearts and thinking minds in animals. And this has not only been to their detriment but ours, for when we disregard the worth of “others”, a part of our heart shuts down, and in a world desperate for a kinder way of living, that’s the last thing we need to happen.

The animals at sanctuaries like Edgar’s Mission are the lucky ones, those who have escaped industry and commodification, those who have fallen through cracks in our society yet somehow have managed to survive, and human kindness has helped navigate them to our sanctuary gates. On this day, gathered as we are, please spare more than a thought for the not-so-lucky ones, those animals encased in fecal matter as so many of them are, whose eyes and lungs sear from the effects of ammonia due to the build-up of excrement that has become their world. Their unimaginably cramped and barren conditions that thwarts their ability to move about, to travel the vast distances their biology tells them to, or to even find a comfortable and clean area to rest, with stomachs aching from sea-sickness, or hunger and thirst, with unfamiliar sights, sounds and even food, with no terra firma to stand on and no meaningful animal protection laws to safeguard them.

The animals consigned to the live export trade could be forgiven for thinking that our species is the devil incarnate. I ask you all, as you leave here today, to dig deep into your humanity, surface with its greatness in your heart and mind, and vote to prove to these animals that we are not; that we are compassionate and that we are kind and that we are thinking of them.