In 1974, philosopher Thomas Nagel posed the question: “What is it like to be a bat?” Nagel went on to posit that we cannot ever fully understand what it is like to be a bat because we humans will always view a “batty” world through our human lens. The subjective nature of the conscious experience of a bat escapes our physical descriptions of observable behaviour, and so we cannot know what is actually going on in the mind of the bat.

Adding credence that Nagel’s view is correct is our own difficulty in fully appreciating how others experience the world, including our own species, attempting, as we do, to apply our own subjective experiences (remember the white gold/blue black dress controversy – and this was a simple visual experience alone). Understanding the grief of another, the joy of another, the fear of another and so on, try as we might and empathise as we may, we cannot with the fullest of certainty ever know we have hit the nail completely on the head to fully understand the experiences of another.

But we know enough. With science weighing objectively in on our subjective experiences comes a defining commonality of evolutionary continuity, neural pathways, and need of nourishment, shelter and sleep, to name a few. We can glean enough meaningful information to appreciate, to a great measure, how another experiences their world. And enough to know how the world around a person (or bat or sheep) will impact upon them.

I often hear people say, when referring to a “hand and house” reared lamb – an animal who happily wanders into the house and takes their rightful position on the couch, or who races crazily about the backyard one moment then amiably follows their “master” another – “Oh, he thinks he’s a dog”. But does he? “Think”, most certainly yes – but a dog? After all, the word “dog” is merely a label the English/American language has bestowed on an animal driven by canine genetics, one with four legs, two ears (generally floppy), a waggy tail and an uncanny habit of sniffing the rear ends of other dogs. Moreover, the behaviours that caused the “hand and house” reared lamb to be described as a dog are ones we typically associate with dogs and not lambs or sheep for that matter (without the butt sniffing of course). But are they the sole preserve of the dog, or is it this more a case of opportunity? Most sheep are considered “livestock” or “production animals”, animals that we humans have bred in vast numbers, and generally only view wandering about vast paddocks and fields, and most certainly not as animals with individual and personable personalities. They are animals who we humans have viewed with a psychological need to not consider their subjective experiences, lest this cause a seismic shift for how sheep are treated and our intended use of them.

But come visit Edgar’s Mission (please do book first) and chances are you will be greeted by the Lady in the Hat (me), Vet Nurse Ruby (the dog) and a perky young lamb named Leo Tolstoy trotting right beside. Leo Tolstoy readily recognises his own name, he will look towards you in acknowledgement, and if he feels so inclined, he will wander over (that is the nature of Edgar’s Mission, their world, as much as possible, is always of the animal’s choosing). Leo Tolstoy is quick to run up the stairs to the office, something that surprises so many. But for Leo it is the most natural of things – after all, how else is he expected to get in and take his place in his bed! When I head on into town for tea with my mum, Leo Tolstoy comes along too. He travels in his carrier in the back of my van. At first he would protest, but he quickly caught on, so much so that on arrival at my mum’s house, after alighting from the vehicle, he races unguided to the front door where he promptly scratches at it with his hoof to be let inside (he has his human folk well trained and we are quick to oblige him). Once inside he checks out each room, much in the same way a curious small child “sticky beaks” at their new surrounds. But this is no random search: Leo Tolstoy takes the same well-defined path each time – mum’s room first, then the bathroom, then out through the kitchen into the lounge room then back to the kitchen again. Here he searches for the blue bowl, as the blue bowl never fails to deliver his food, and in he tucks, tail wagging in consummate delight. Many observing this behaviour would be taken aback, expecting such from a dog. But not a sheep. But Leo Tolstoy doesn’t know that; what he does know is the world according to Leo Tolstoy.

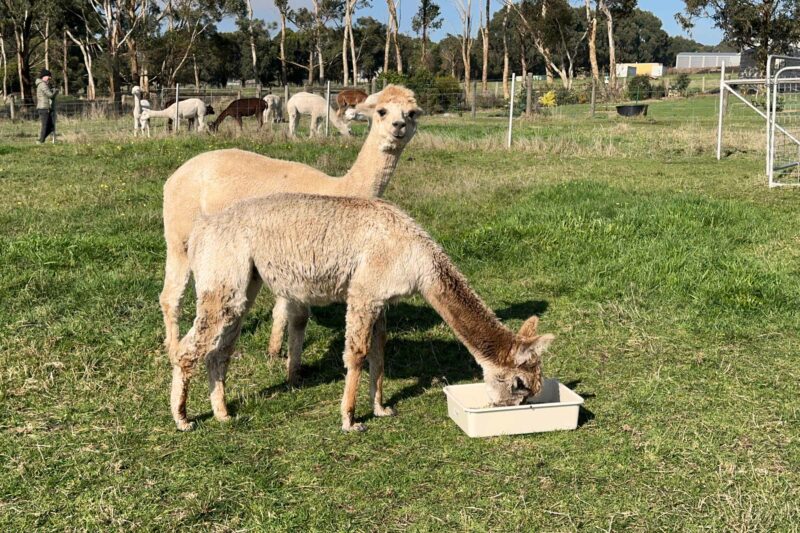

This not only gives rise to appreciating their unique and individual personalities, but how the world around them impacts upon them – a world so often of our making. Even within a group of sheep you will find differences, and this can be further broken down to differences between the “friendly” sheep, the “timid” sheep, the “brave” sheep etc. Naming them all as we do at Edgar’s Mission, we often acknowledge their personality – Captain Courageous, who bravely escaped from an abattoir and ran for his life; Spartacus, a sheep previously used for experimentation, who boldly stamps his hoof, telling you to stand down; Honey, an oh-so-sweet little ewe; and Lemonade, whose personality daily threatens to bubble over.

There is no doubt that seeing sheep in sanctuary settings casts doubt on the traditional world view of sheep, a view that hurls them all into the fold of dull, dim-witted and stupid animals. But they are far from this convenient view. Although nature and human selective breeding have given them few defences against a big bad world, they do have one – their smarts. And sheep are smart; given the chance you can find this out too (you can also find they’re affectionate and playful, with each putting their own spin on these things). It is lamentably more than an “old wives’ tale” that the smart sheep, the one who works out how to open the gate and let his buddies out to greener pastures, will be the first one sent to market.

Yet creative and problem solving they are, just as they too possess a range of emotions akin to our own. All this has great implications for much of our treatment of sheep. And just as a person suddenly cast in a foreign country with a different language and culture struggles to understand those around them, there exists a need to, a very real and urgent one. One of our greatest human desires in this world is to be understood. What if this is so too for a sheep? Given the great advancement of science and human thought since Nagel posed his thought question almost 50 years ago, it’s high time to reassess our view of what it means to be a sheep and recognise that there is a lot more going on in that sheepish brain than we once thought. Kindness can be our greatest tool to reach it. Coming to know Leo Tolstoy as I have, I truly believe we’d be batty to do any less.