From the vantage point of my window I spied a sheep lying unusually still in the paddock. During the preparation of my evening meal I was able to watch some more. What started as mild curiosity slowly gave way to increasing levels of concern, as the sheep had not moved for the longest of times despite his flock mates doing so some time before. Giving credence to my angst was the presence of a crow now sitting on the animal – something that is so often the harbinger of something very bad. His slow pecking movements were indeed red flags to my concern. Yet the sheep appeared oblivious to this intrusion. As the crow pecked more feverishly, there was still no reaction and I started for the door. By the time I hit the gate of the paddock my heart had begun to race. As I raced down the hill I picked up speed, then I picked up angst, all fuelling my belief that something was seriously wrong. With each stride my once-determined screams were reduced to pitifully gasped yells of “Shoo, damn you, shoo”. But the crow refused to fly, pecking more feverishly as if in defiance of my protest. Knowing the grisly wont of crows for pecking out the eyes of hapless downed sheep, not even extending them the courtesy of death, I prayed I was not too late to save my beautiful friend. What I was to gain in ground as I ran only reduced my hope to despair. Tears began to well and my heart began to ache: “How could this happen? Life is so darn unfair.”

But then, just as I was about to sink to my wobbly knees, the “crow” was no more. In his place was the big black flapping ear of the snoring black-faced Suffolk sheep I know and love and who is ironically named Rorschach, roused abruptly from his summer siesta by some buffoon bolting down the paddock, screaming like a banshee. Instantly he stood, and with his belief I was stark mad now confirmed, he sprinted off. I’m not sure who got the biggest shock; however, mine was most certainly of the best kind.

There is no doubt we humans are natural storytellers, from the unknown author of the Epic of Gilgamesh, through Shakespeare to Steinbeck, Scott Fitzgerald, Dickens, Dahl, King, Attwood, Rowling and countless others I have overlooked. And whether is it gathered around a campfire, bar-room table, family gathering or people just getting together, we love a good tale. Stories inform, engage, empower and captivate; they forge bonds amongst people; they are powerful allies to sharing culture, history and values.

So powerful are these stories we are able to find the courage to walk on hot coals without feeling any pain, to be swept up in the charisma of a cult, or to convince ourselves that the flapping black ear of a sheep is a sinister crow attacking a dead animal.

But of the stories we tell ourselves, it is not so much the facts of the story that shape our belief, rather, the facts that support our belief that shape the story. We indeed are, as a species, far better at taking on facts that support our belief than those that challenge it. That we will believe what we want to believe, regardless of how ever much supporting and persuasive evidence there is to the contrary, is proof of this. This phenomenon is known as “confirmation bias”. The first drafts of our beliefs are laid down in our genes and in the womb, built upon by our early childhood experiences and then solidified by those around us as we grow, so much so until they become facts, not necessarily “the” facts, just our facts. This is why people good at heart believe and even do bad things: why people prefer to listen to the stories of their “tribe” and allow this to inform their opinion more than a truer narrative. Sadly too, many a good character has suffered at the hands of this – it goes by the name of gossip.

Our human desire to belong to a group has its roots in the evolution of our species, a species that recognised the benefits offered by group membership in terms of safety in numbers, a more abundant food supply and sex. To not go along with the group belief meant vulnerability by way of exclusion from this safety net. But times have moved on; we are no longer pursued by sabre-toothed tigers; we have easily obtainable food sources; and there is, after all, Tinder. And although belonging to a group has its distinct advantages, what has greatly progressed the evolution of our humanity have been those individuals charged with individual thought, those who courageously have embraced the ability to look inward and ask:

We do not have to completely understand all the intricacies and facts before forming a belief. After all, we believe that electricity works, but who completely understands how it works? Yet we owe it to our ourselves and our world to shine a light upon the often unpalatable consequences of our beliefs and ask: “Do they make sense?”

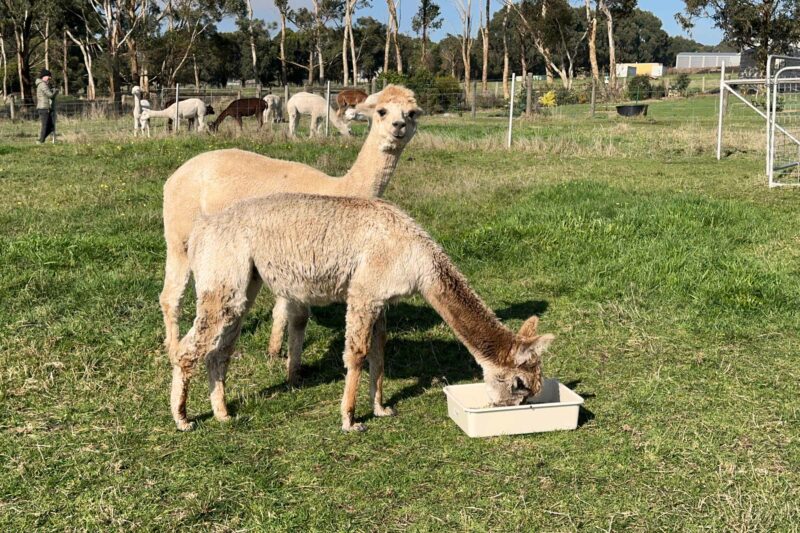

And from my vantage point of the world, so often the casualties of ingrained societal beliefs are animals – those less powerful, least heard and more vulnerable amongst us. In my recent experience with Rorschach I find a perfect metaphor for this – despite them being very much alive, when it comes to our consideration of them, they are “dead” and nothing will convince us otherwise. In fact, the more we move forward with our lives and our habits, the more traction our beliefs have. But before we open our minds to who they really are, we must open our hearts, and this is hard to do from afar because the tyranny of distance equates to a chasm of untruths. The only thing that can shatter this is to step closer, much closer, and look an animal in the eye – for you will see, staring right back at you, a thinking, feeling, living, breathing being who thinks you are stark mad for thinking otherwise.